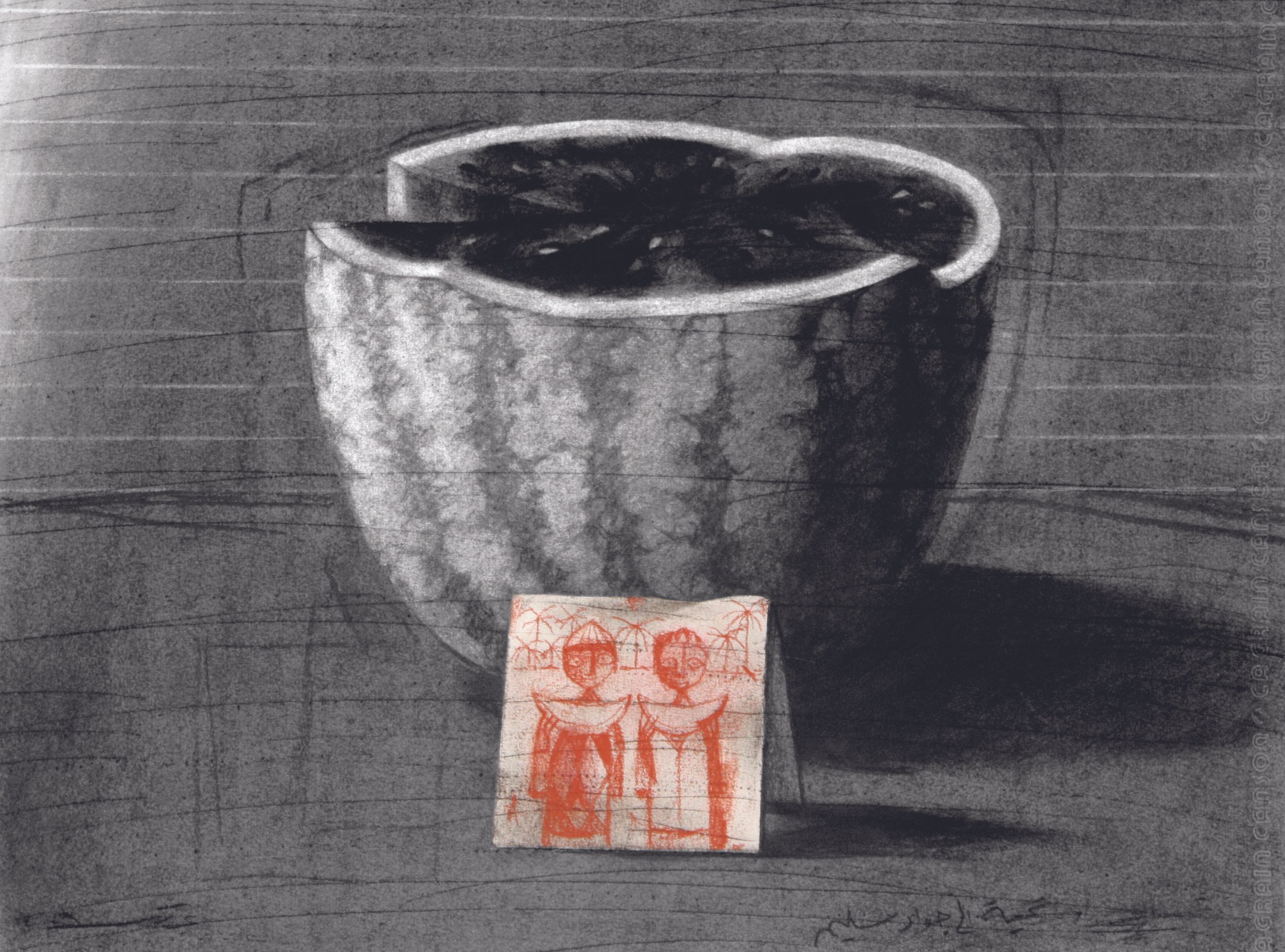

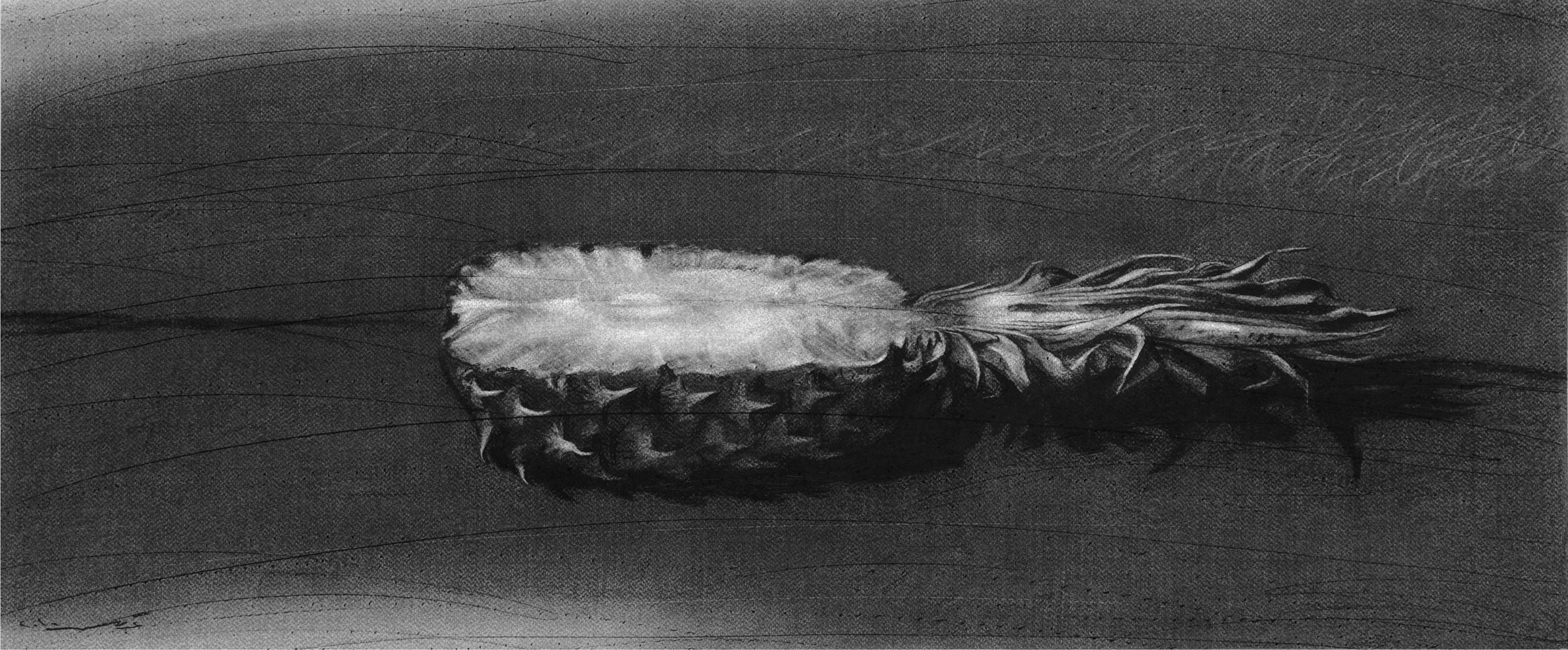

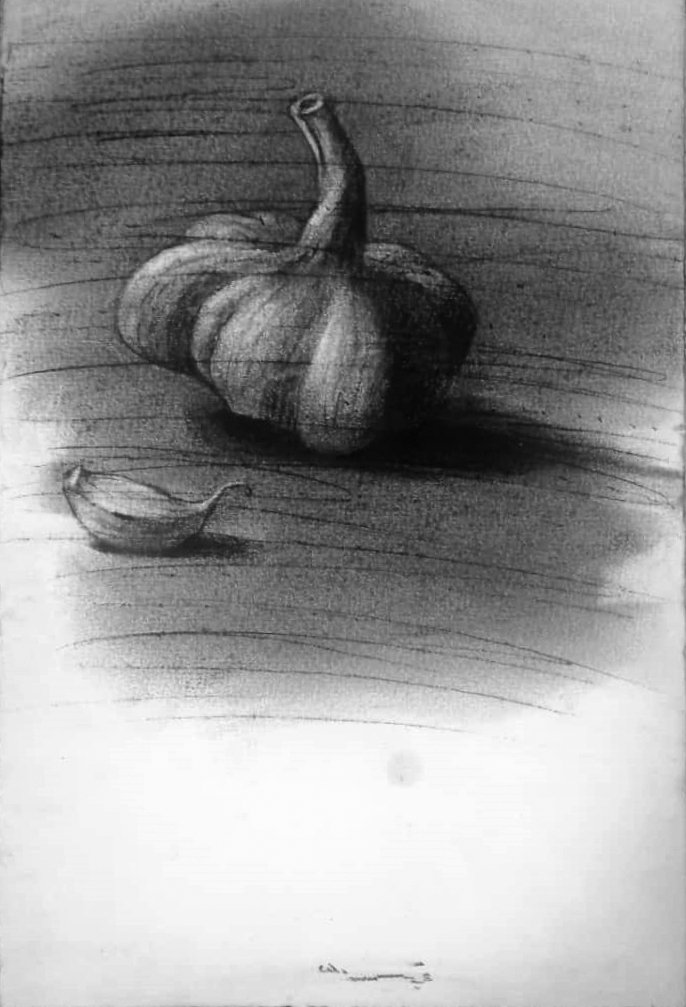

In 1995, Abdelké renounced color to sink into the abysmal eternity of black and white, giving his work the appearance of a tombstone. Struggling to expel death while exposing it, and striving to exalt the lives of those who have lost it. He mourns his beloved land by drawing realistic still lifes with charcoal, very dark and very large, which nevertheless allow a diffuse light to filter through, sparked by white flashes whose origin is off-camera, like announcements of mourning and truth.

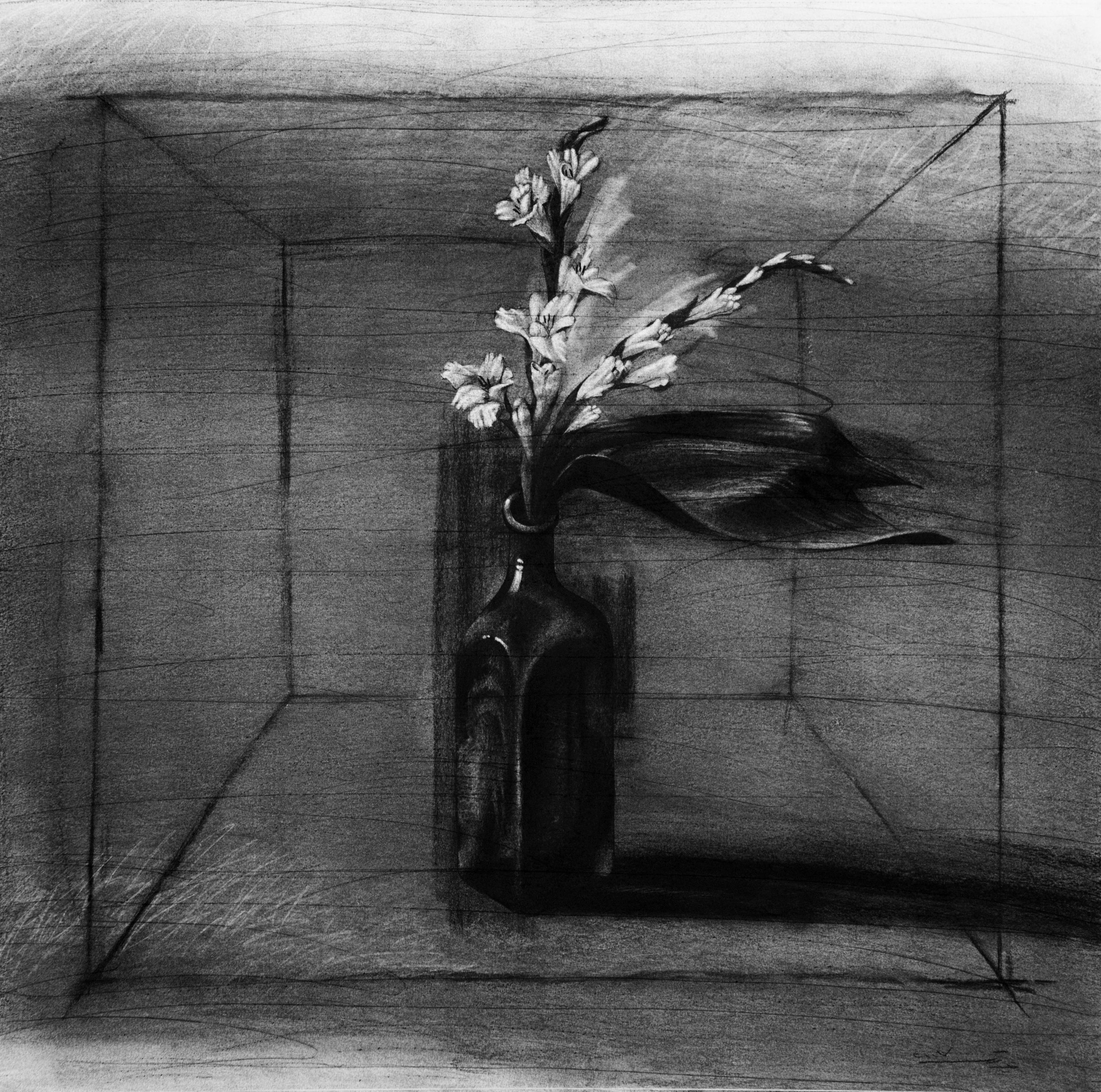

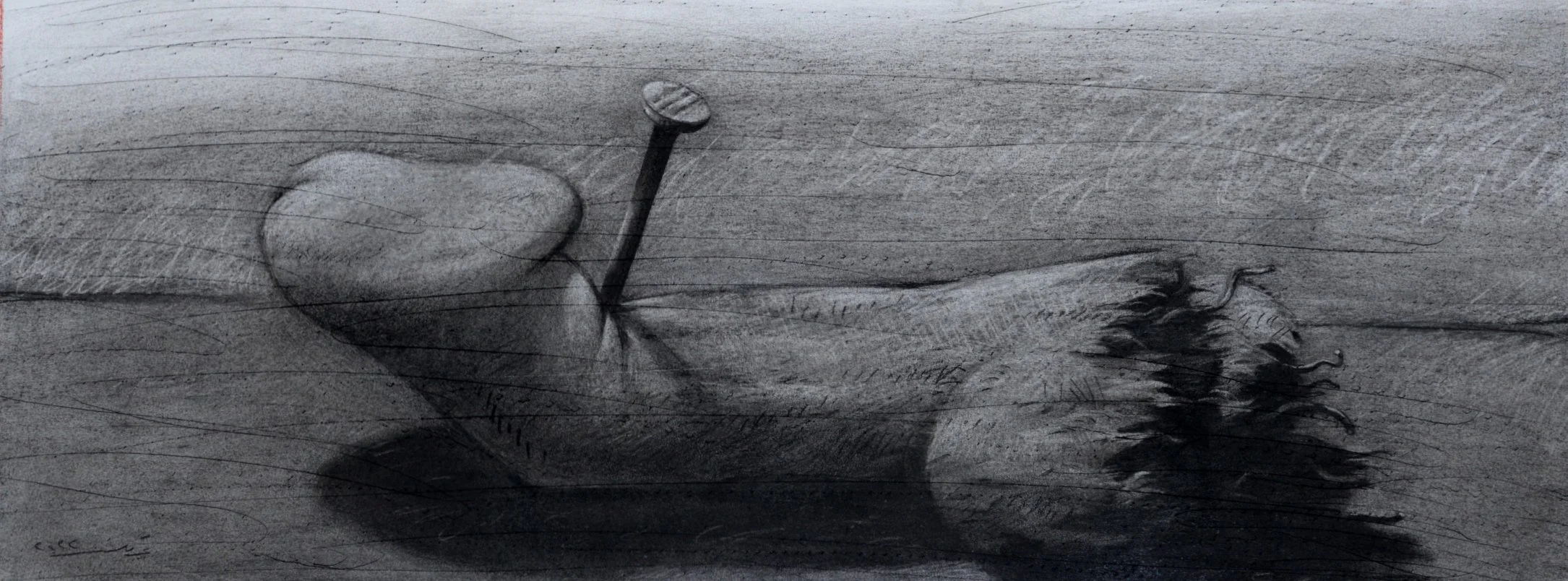

Precise, sharp and as if hatched with a scalpel, his drawing uses large strokes and angry scratches, as if he were incising veins in ancient stone. Allegorically transposing the assassin's gesture by inflicting it on an object or a plant, the Nailed Brush, the Cactus (disemboweled by a knife) from 2009 or even the Pierced Heart (by a skewer) from 2012 evoke the sacrifice of the Syrian land, which continues to crucify its own children - as the caliph of Baghdad did in the 10th century by condemning the Sufi mystic al-Hallaj to the cross (on the grounds that he had publicly proclaimed to be the Truth). Leaving the bias of things to go towards other black flowers of melancholy, Abdelké then traces, with Birds of Paradise (2007) or Bottle and Flowers (2014), charcoal “portraits” of cut flowers, like stems of barbed wire growing into petals of black blood.

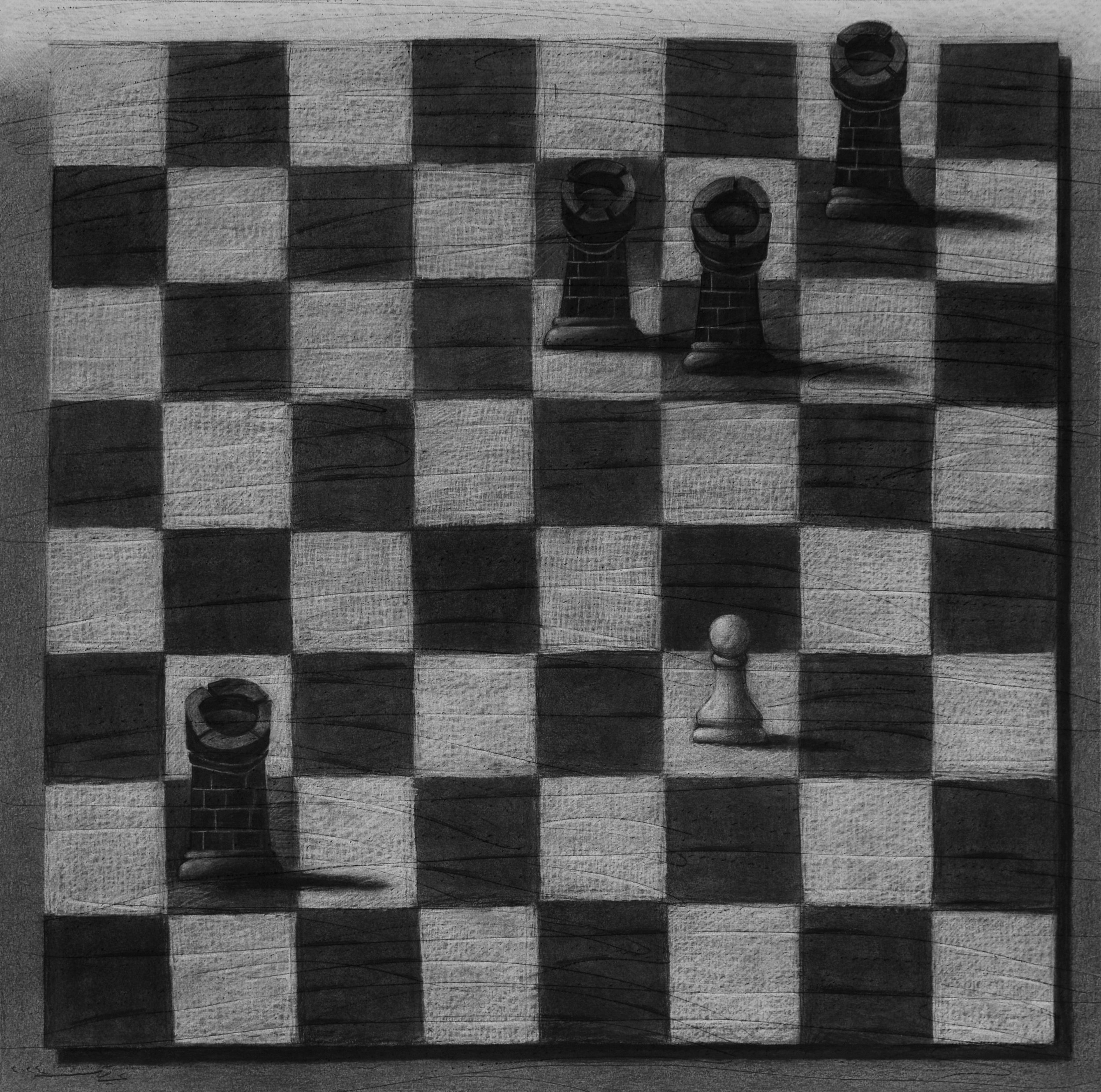

At the same time, the artist identifies the martyrdom of his people with that of animals disemboweled at random on the battlefield. Representing a goat's head tied up in ropes, with a Tied up Skull (2007), he builds with The Knife and the Bird (2007) or Bird and Checkerboard (2010) a tomb of birds.

Abdelké has not shied away from taking on authorities in the past and his body of works from 2011 to 2023 is testament to that.

While activists and state journalists are out on the front line recording every shell blast and clash, Abdelké has found his own more personal way of reporting on the hardships of fellow Syrians, using charcoal and paper.

"I think all the works in one way or another try to express the concerns and emotions of the ordinary Syrian citizen amid this huge river of blood.”

Many of the works are abstract rather than overtly political. Many of them focus on small, intimate moments, rather than trying to make sweeping statements about a civil war that has killed 500,000 people, driven millions from their homes and devastated whole districts of Syrian cities.

"The whole situation is an open-ended crisis. It affects all civilians, even those who consider themselves outside of the conflict."

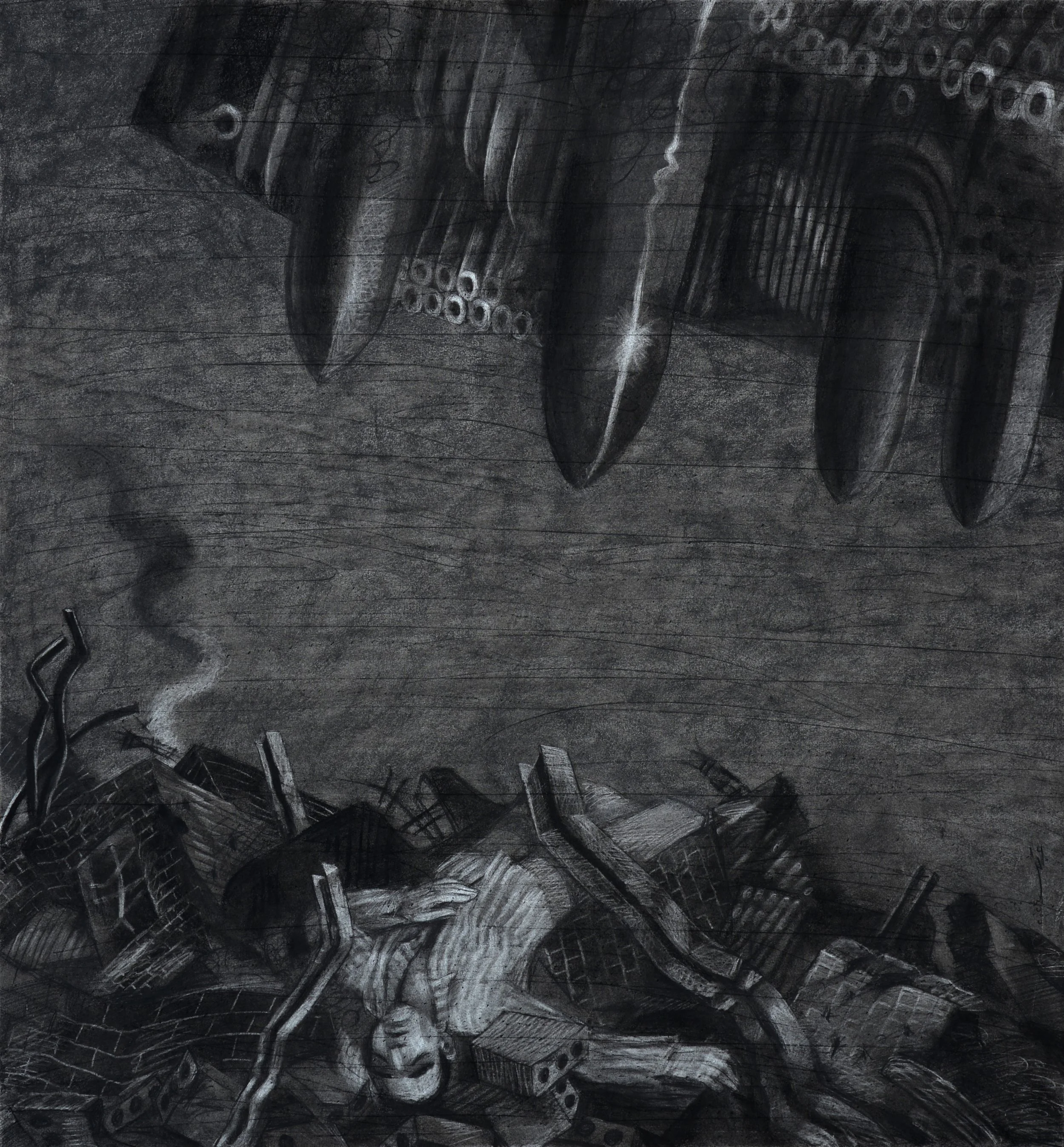

Diaries of Gaza. 2024. Charcoal on paper, 105x96cm.

Dara's 13th of April 2011. 2024. Charcoal on paper, 200x150cm.

Martyr From Dara'a. 2011. Charcoal on paper, 51.5x69cm.

Martyr From Dara'a. 2011. Charcoal on paper, 154.5x149cm.

Martyr From Douma. 2013. Charcoal on paper, 99.7x102cm.

Martyr From Daray'ya. 2013. Charcoal on paper, 99.7x100cm.

Martyr From Al-Tahrir Square. 2013. Charcoal on paper, 100X100cm.

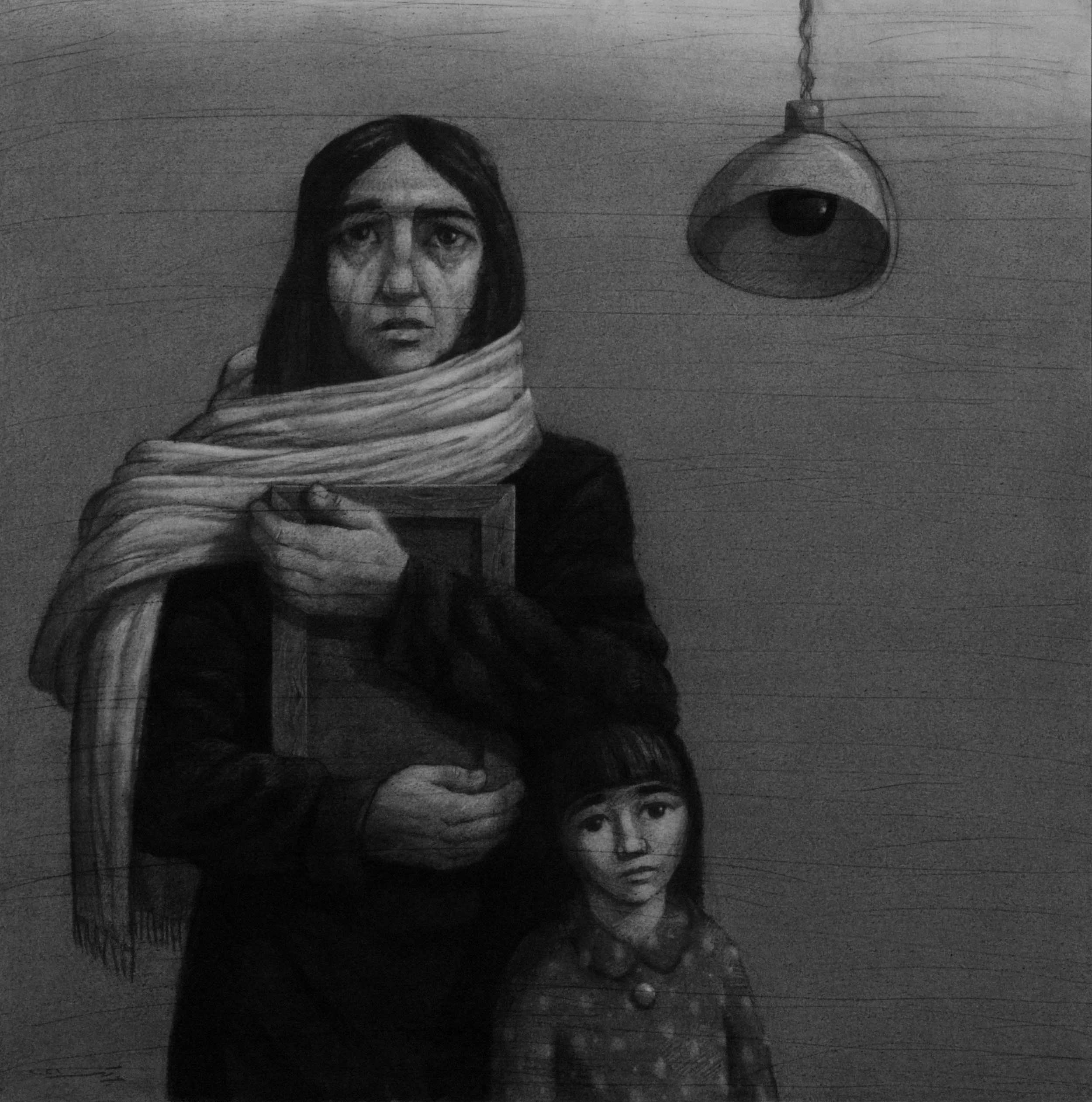

The Martyr's Mother. 2012. Charcoal on paper, 100x101.2cm.

Refugee. 2021. Charcoal on paper, 102X102cm.

At The Prison’s Door. 2021. Charcoal on paper, 194x146cm

Skull. 2014. Charcoal on paper, 45x34.2cm.

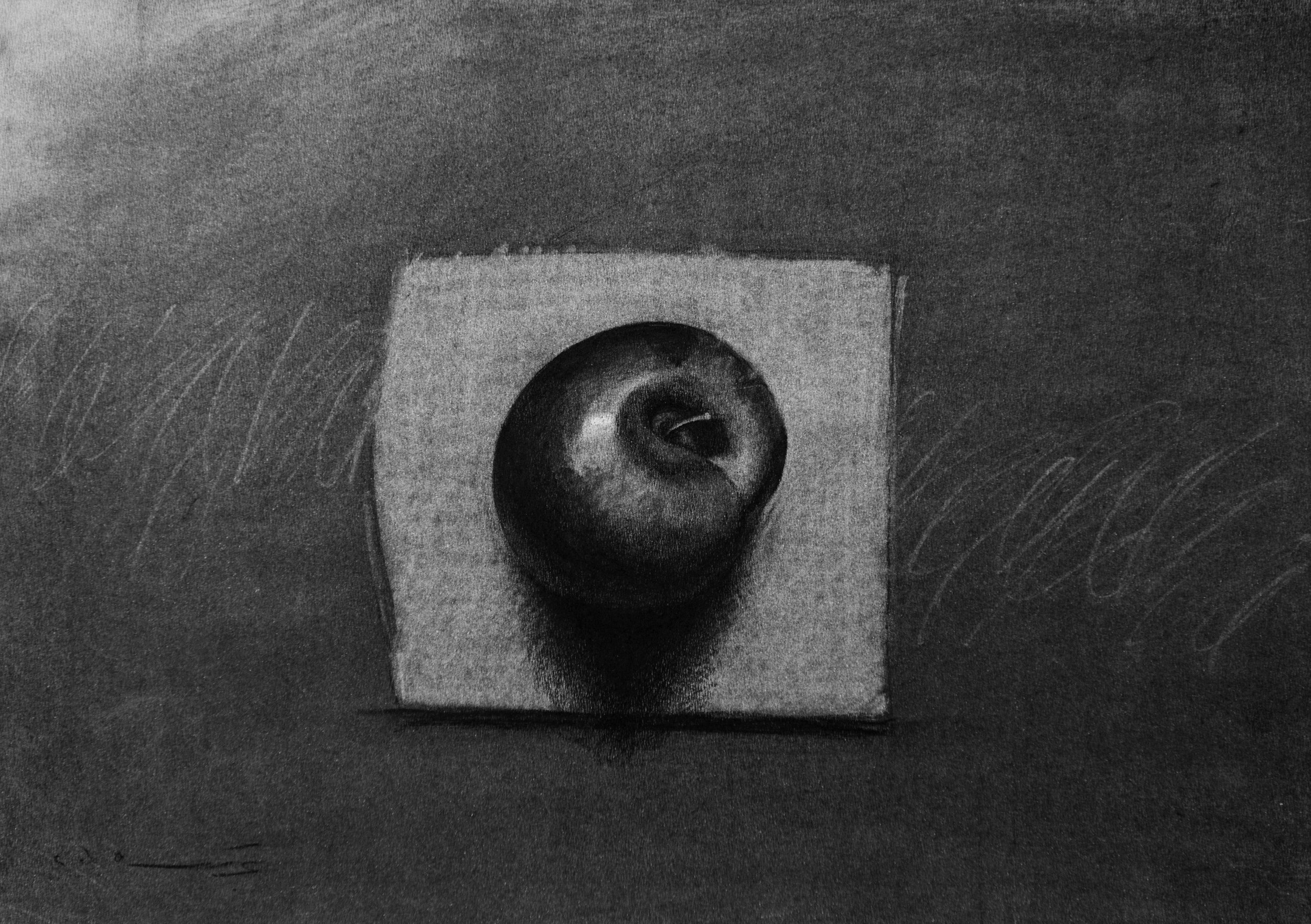

Apple. 2014. Charcoal on paper, 44x34.5cm.

Lily. 2012. Charcoal on paper, 25.5X45cm.

Tea Pot. 2014. Charcoal on paper, 43.7X34.5cm.

Lily and Bottle. 2014. Charcoal on paper, 36.5x53.3cm.

Sardine. 2014. Charcoal on paper, 41x41cm.

Sugar Pot. 2014. Charcoal on paper, 42.6X35.3cm.

Ink Bottle. 2014. Charcoal on paper, 45.5X34.5cm.

Flowers. 2014. Charcoal on paper, 100x43cm.

Apple. 2015. Charcoal on paper, 31x45cm.

Lemon Branch. 2014. Charcoal on paper, 100x100cm.

Cable. 2015. Charcoal on paper, 100x100cm.

Brush. 2015. Charcoal on paper, 101x40.8cm.

Shoe. 2015. Charcoal on paper, 150x150cm.

Skull. 2015. Charcoal on paper, 100x100cm.

Apple. 2015. Charcoal on paper, 106x35cm.

Shell in a Box. 2016. Charcoal on paper, 67.7x40.5cm.

Dead Bird and A Cleaver. 2016. Charcoal on paper, 99.7x101.2cm.

Two Knives. 2016. Charcoal on paper, 100x100cm.

Roses. 2016. Charcoal on paper, 102.3x100cm.

Lilies. 2017. Charcoal on paper, 102x103cm.

Dead Branch. 2018. Charcoal on paper, 101.5x103cm.

Bone. 2018. Charcoal on paper, 146.3x195.5cm.

Colouring Tube. 2019. Charcoal on paper, 32.5x50cm.

Jars. 2020. Charcoal on paper, 43.5x54cm.

Phallus. 2022. Charcoal on paper, 101x40cm

Fish in Plate. 2000. Charcoal on paper, 103x103cm.

Shoe 9. 2004. Charcoal on paper, 145x191cm.

Shoe 10. 2005. Charcoal on paper, 243.5x144cm.

Shoe 3. 2001. Charcoal on paper, 193x100cm.

Fish and Nail. 2008. Charcoal on paper, 38x101cm.

Fish in a box. 2008. Charcoal on paper, 150x150cm.

Two Lilies in A Box. 2009. Charcoal on paper, 100x100cm.

Salute To Jawad Salim. 2009. Charcoal on paper, 37x50cm.

Salute To Jawad Salim. 2009. Charcoal on paper, 37x50cm.

Pineapple. 2010. Charcoal on paper, 50x100cm.

Garlic. 2010. Charcoal on paper, 25x16.5cm.

Skull and Butterfly. 2010. Charcoal on paper, 150x150cm.

Red Cabbage. 2011. Charcoal on paper, 108.5x147cm.

Pierced Heart. 2011. Charcoal on paper, 108.5x147cm.

Chess Board. 2024. Charcoal on paper, 100x101cm.